There is no need for TOS on ebooks that take away users rights.

| Freedom for IP Discussion List |

There is no need for TOS on ebooks that take away users rights.

I would like to thank Bill Hinsee for all his great legal work this summer at FFIP. He worked on projects including: Bilski – patent reform, Fair Use & Bad Faith, privacy labels, privacy case law research, Viacom v. Youtube research, and file sharing case law research. Bill was a great help this summer and will be a strong addition to the IP legal community and the free culture community.

Bill is a rising 2L at Boston Univeristy Law and a graduate of the Masters of Science in Information Management program at the University of Washington’s Ischool. He is also a photographer with a photo blog that uses creative commons licenses.

Photo: Bill Hinsee under CC Attribution Noncommercial No Derivative

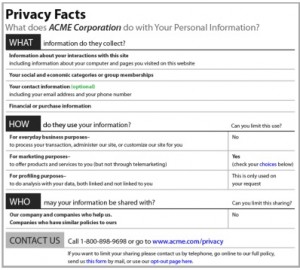

Website privacy policies can be complicated and confusing. The lack of a standard in both presentation and terminology makes it difficult for the average consumer to understand a website’s privacy policy, an understanding which is necessary to make an informed choice whether to use a particular website’s services. In A “Nutrition Label” for Privacy, Patrick Kelly, Joanna Bresee, Lorrie Cranor and Robert Reeder present a way to display online privacy policies in a consumer friendly manner in the spirit of the ubiquitous nutrition label.

The authors’ proposed label, the “Privacy Nutrition Label”, uses a grid to display the privacy policy with the rows displaying the types of information collected and the columns showing how the information might be used and to whom the information might be shared. A privacy symbol is displayed in the intersection of each row and column representing the severity of the privacy practice. The label consists of ten rows of information collected with five ways of using the information and two outlets for sharing the information totaling seventy cells, each displaying a privacy symbol. This is a large amount of information to sort through no matter how cleanly organized. Multiply this by every website that you might interact and do business with and it only gets worse. I personally prefer an earlier iteration of the authors’ label, the “Simplified Label”, which displays the privacy policy in a series of Yes/No statements. Although it lacks the detail of the grid and may exaggerate the permissiveness of the policy because of grouping categories together for simplicity, it is easy to understand and quick to read. A possible compromise might be to allow the Yes/No statement to be expanded into a more detailed breakdown if the user feels the policy is too permissive and wants to know more about it.

|

|

The authors’ project is a great start to simplify privacy policies but should be expanded to address two more concerns, the permanency of the information collected and mutability of the privacy policy. The first issue is simply how long the company will store the information collected about you. If I purchase a book from an online seller, how long will the company keep my credit card information? How long will it keep my address and phone number? This can be addressed simply by supplying a column in the “Privacy Nutrition Label” to display the length of time data is kept or a time range in the “Simplified Label” that can be expanded for more detail if desired. The second issue addresses what happens when the company changes its privacy policy. Will the company notify the consumers whose information the company has already collected when it makes a change to the privacy policy? How will the consumers know the policy has changed otherwise? What happens to the information already collected? Will that information now be subject to the new terms? A Big Mac purchased under the “terms” of one nutrition label is not going to be retroactively affected if McDonalds changes the recipe at a later date whereas data residing on Facebook might. The solution to this is a mechanism to show how and when a policy has changed.

The has developed to address this very issue. TOSBack monitors the privacy policies of various websites and publishes the changes made to those policies. Something like this would be very helpful if incorporated into the privacy label itself to allow the consumer to see a policy change when revisiting a particular website. This of course would not help a consumer who uses a website for a one-time purchase and never returns but it is a start.

A larger problem with the privacy label project in general is with its adoption. A project such as this is only as useful as the size of its implemented base. Moreover, companies must agree on how to implement it. It would defeat the purpose to have different companies presenting their privacy labels differently, such as using different colors or symbols for privacy statuses. Such inconsistencies would only further complicate and confuse the consumer. Maybe this is a case where government regulation would be helpful. A regulatory agency such as the Federal Trade Commission could ensure that the use of such labels were widespread as well as preventing the proliferation of dissimilar privacy labels.

Overall the authors’ project is a noble one and one that I think whose time has come. Consumers deserve to understand the policies surrounding the data collected about them without having to struggle through pages and pages and legalese. The keys to the project’s success are adoption and standardization, without which the project is simply a great idea.

When Shepard Fairey (“Fairey”) first sought a Declaratory Judgment against The Associated Press (“AP”) regarding Fairey’s use of an AP photograph, the Fair Use Project at the Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society took the case representing Fairey. The heart of the case was whether Fairey’s use of the AP photograph fell within the “fair use” exception of the copyright law, insulating Fairey from a possible copyright infringement claim brought by AP.

The purpose of copyright law is to spur innovation and creativity by granting some protection to a creator’s works thereby giving the creator an incentive to create. Because copyright law restricts the free speech rights of others, the “fair use” exception provides balance by allowing others some access to copyrighted works so that they may create new works based upon them. As conveyed by Justice Story, “[i]n truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.” Simply put, innovation is the building upon the foundation laid by those before us.

Fairey’s case appeared to be a good test to clarify “fair use” doctrine at a time in which digital technologies have proliferated the creation of transformative works. Fairey used an AP photograph as the foundation for a graphic of Barak Obama that Fairey used in a series of posters. Fairey’s use appeared capable of passing the courts’ implementation of the “” evaluation (purpose and character of use, nature of copyrighted work, amount and substantiality of use, and effect of use on potential market) because the highly transformative nature of Fairey’s work might have propelled it beyond reach of the other factors. Unfortunately, the case was tarnished by Fairey’s actions resulting in the withdrawal of Fairey’s attorneys and the suggestion by the judge hearing the case for the parties to settle. This does not bode well for Fairey’s case.

So what went wrong?

Fairey originally claimed that he used an AP photo containing images of both George Clooney and Barack Obama as a reference in creating Fairey’s artwork and specifically denied using an AP photo of Obama alone (the “Obama photo”). However, Fairey later claimed that there was some confusion over which photo was used and that he actually did use the “Obama photo”. The photo used was relevant because, in general, the less one uses of a copyrighted work, the better the case is for “fair use.” If Fairey used the photo of Clooney and Obama, the amount of the copyrighted work used (roughly half) would have been less than had Fairey used the entire “Obama” photo as the reference. However, even the complete usage of a copyrighted work does not necessarily preclude “fair use” so while using a different photograph might have helped the case, Fairey’s usage may have still been ruled “fair use” nonetheless. That was before Fairey’s next move.

Rather than informing his attorneys of the error, Fairey attempted to cover it up by erasing the computer files that were used to make the graphic from the “Obama photo.” Fairey went so far as to create new documents using the AP photograph of Clooney and Obama in order to support his claim of using that photograph. Destruction of evidence and deceit does not bode well when defending a “fair use” claim and it is arguably what may decide this case.

This is because the Supreme Court has stated:

Also relevant to the “character” of the use is “the propriety of the defendant’s conduct.” “Fair use presupposes ‘good faith’ and ‘fair dealing.’”

Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539, 562 (1985) (quoting 3 Nimmer on Copyright § 13.05[A], at 13-72 and Time, Inc. v. Bernard Geis Associates, 293 F. Supp 130, 146 (S.D.N.Y. 1968)).

So what exactly is good faith? As my contracts professor once said, good faith is not defined so much as what it is but rather what it is not. That is, good faith is the absence of bad faith.

Despite the Supreme Court’s affirmation of the relevance of good faith in “fair use” evaluations, the courts have not agreed upon how much weight it should be given. In the case cited by the Supreme Court in its affirmation, the Southern District of New York Court ruled that the defendant’s use was “fair use” because the “fair use” was strong enough to discount the defendant’s bad faith in appropriating the materials (which could have been appropriated by other means). Time, Inc. v. Bernard Geis Assoc., 293 F. Supp. 130 (S.D.N.Y. 1968). The Supreme Court, in its own case at hand, ruled against the defendant, in part, because the defendant was trying to “scoop” the story out from under the plaintiff who had legitimately licensed the story. Harper & Row Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985).

More recently, the Second Circuit ruled in favor of a defendant despite the defendant’s bad faith in obtaining the material in an unauthorized manner, stating that “a finding of bad faith is not to be weighed very heavily . . . and cannot be made central to fair use analysis.” NXIVM Corp. v. Ross Institute, 364 F.3d 471 (2nd Cir. 2004). The Second Circuit then stated that it awaits clearer guidance from the Supreme Court. Id. In another case, the District Court of Nevada contrasted the bad faith of the plaintiff with the defendant’s good faith stating that it added further weight in ruling for defendant’s fair use. Field v. Google, Inc., 412 F. Supp. 2d 1106, 1123 (D. Nev. 2006).

Although the impact of good faith may not be predictable in Fairey’s case, keep in mind that the good faith discussions in most of the above cases have been centered on the acquisition of the material. Fairey’s destruction of evidence and deceit are of a different type entirely and may prove to be the deciding factor.

In copyright we need a simple principle from property law to be added, Abandonment. If you are no longer using a work it should be liberated into the public domain so that others can use it as the copyright act intend. Copyright was meant to bring works forward not to let them rot. A local lawyer/gamer geek I know is spending this week on Abandonware :

What is abandonware? Like many programs which were released in the early to mid nineties, abandonware is a program, usually a game, which appears to have been “abandoned” by the owners. Much like shareware, freeware, and malware, abandonware was named by taking the identifying suffix “-ware” and adding the descriptive verb which best describes how the software is viewed by the end user community.

Some abandonware started out as freeware, released by small companies or a promotional release that incorporated a consumer tie-in in an over-the-top way. Casual or mobile games released as tie-ins to other entertainment properties tend to be the closest parallel today, although the open source community has a large number of these types of games available as well. Games which encouraged user generated content such as level designs often allowed the users to share the levels without extra cost, although a copy of the underlying game itself was required in order to use the free levels.

Other abandonware started as shareware, which tended to be smaller demos or free levels given out by the game company to get players interested in the proprietary game. It wasn’t the full game or a totally free version, hence the division in naming, but was still intended to have more of a viral marketing presence than possible through just magazine or radio ads. Doom and Duke Nukem still have demo versions floating around online, and the need to test a product before buying it has become ridiculously easy now that so many games are delivered digitally, without cartridge, dongle, or paper manual.

Read the rest at GirlGamerEsq